My first full time job and how it gave me my current view of business and world leaders.

In the late 1970s, I took my first full time job that dropped me straight into New York business culture. I was young, ambitious, and eager to prove myself. What I didn’t yet understand was that New York doesn’t reward potential—it rewards results, endurance, and toughness. I worked directly for a senior VP executive who embodied that world perfectly. He was brilliant, driven, successful—and also unreasonable, foul-mouthed, demanding, and at times cruel. Every day felt like a test, not just of skill, but of nerve.

That experience nearly broke me.

It also shaped me.I’ve dealt directly with a certain kind of businessman before.

The kind who comes out of New York hard, fast, demanding, impatient, and unapologetic.

The kind who believes pressure reveals competence.

The kind who pushes people past comfort—and sometimes past what feels reasonable.

I learned that lesson early in my career, long before politics ever entered my life.

I learned how high-pressure leadership actually works.

I learned how aggressive decision-makers think.

And I learned something that has stayed with me ever since: results and personality are not the same thing.

Over the course of my career, I went on to work closely with many leaders—CEOs, presidents, senior vice presidents, founders. Different industries, different temperaments. But one trait kept showing up among people who truly ran large organizations: they were blunt, critical, highly confident, and completely uninterested in being liked.

Note: This piece is an exploration of leadership style and human behavior, not an endorsement of any individual or every action they’ve taken.

Ironically, that’s the very trait that gets Donald Trump in trouble all the time.

Let me be clear before going any further: I am not defending Trump’s behavior.

I’m not excusing it, justifying it, or pretending it doesn’t cross lines.

What I’m doing is explaining it—through the lens of lived experience.

When people criticize Trump for “not being presidential” or for saying outrageous things, what I see is something very familiar: a man who has spent his entire adult life fully in charge, fully accountable, and fully responsible for outcomes. When you live that way for decades, you don’t speak in rehearsed language. You don’t filter every sentence through approval committees. You speak in terms of leverage, pressure, and results.

Now stop and think about this for a moment—really let it sink in.

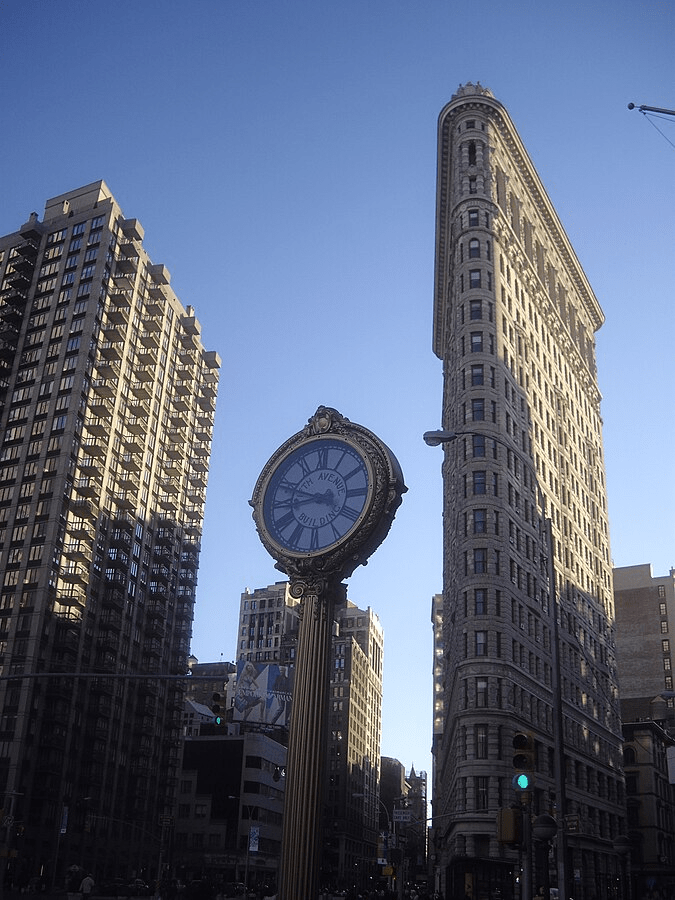

He’s a New York businessman who became the leader of the free world.

He is not a politician by training or temperament. He didn’t come up through party ranks or diplomatic pipelines. He came up through contracts, construction sites, negotiations, lawsuits, wins, and losses. That world doesn’t reward tact—it rewards outcomes.

And that’s why he doesn’t care what people think of him.

His focus has always been on one thing: making America better for its citizens. That doesn’t mean he lacks compassion. It means he believes priorities matter. Leaders of large organizations are wired that way. You take care of your people first, or eventually you fail everyone.

Before Trump entered politics, I didn’t care for him at all. I knew people in the hotel supply, restaurant distribution, and construction industries, and Trump had a reputation. He was famously difficult. He enforced contracts aggressively. If something didn’t meet specifications—even something small—he could withhold payment. Not because it was personal, but because he understood leverage. In some cases, fixing the issue would cost more than walking away.

That wasn’t politics.

That was business.

As The Godfather put it: “It’s not personal. It’s strictly business.”

Trump has lived by that philosophy his entire life—and he carried it into government.

That’s why he can clash with someone one minute and work with them the next. To him, conflict isn’t emotional—it’s transactional. People who haven’t lived in that world often mistake toughness for instability or malice.

There’s another layer here that often gets misunderstood.

Trump is not an outsider because he lacks elite credentials—he doesn’t. He attended Fordham University and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. The difference is not education; it’s wiring. He was shaped by a demanding father and by New York’s hard-edged business environment, not by institutional culture or political etiquette.

While others learned how to navigate systems, Trump learned how to confront them. While classmates absorbed the language of consensus and decorum, he internalized competition, leverage, and survival. That difference never went away. It followed him into business and eventually into politics.

Trump does this instinctively. Sometimes too publicly. Sometimes too sharply. But the instinct itself isn’t unusual among high-level leaders—it’s required.

History is full of leaders who were criticized in their time for being abrasive, blunt, or overly aggressive, yet were effective precisely because they understood power and human nature. Winston Churchill was widely viewed as difficult and temperamental. Margaret Thatcher was labeled cold and ruthless. Ronald Reagan, despite his calm demeanor, was firm and uncompromising when dealing with the Soviet Union—absorbing criticism at home while projecting strength abroad.

And then there was General George S. Patton.

Patton was openly profane, brutally honest, dismissive of weakness, and completely uninterested in politeness. He offended allies, angered superiors, and intimidated subordinates. Yet when the moment demanded speed, decisiveness, and relentless pressure, Patton delivered. He understood something uncomfortable but true: wars are not won by consensus, and enemies are not defeated by sensitivity. They are defeated by clarity of purpose, force of will, and leaders willing to be feared more than liked.

Patton was controversial then—and he still is—but no serious student of history questions his effectiveness when it mattered most.

That reality hasn’t changed. In fact, it has become more relevant.

Today’s world is shaped by leaders like Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, and Kim Jong Un—men who rule through control, intimidation, and force. These are not misunderstood bureaucrats. They do not respond to carefully worded statements or moral lectures. They respond to strength, resolve, and the clear understanding that consequences will follow.

Leaders like that see hesitation as weakness and compromise as opportunity. They test boundaries constantly. And when they sense uncertainty, they push harder.

That’s what traits people criticize in Trump—his bluntness, his confrontational style, his refusal to be intimidated—can function as deterrents on the world stage. He doesn’t speak like a diplomat because he’s not trying to be admired. He’s trying to be taken seriously. His unpredictability, for better or worse, forces adversaries to pause, recalibrate, and think twice.

This doesn’t mean every word is right.

It doesn’t mean every tactic is perfect.

And it certainly doesn’t mean his behavior should be copied in all settings.

But it does mean that, in a world increasingly led by ruthless leader, a leader who is tough as nails is not automatically a liability—it can be a strategic necessity.

Trump is not gentle. He is not polished. He is not careful with words. None of that surprises me, because I’ve worked for men like that. I’ve seen how they think, decide, and operate under pressure.

The mistake people make is judging a lifelong New York businessman by the standards of a lifelong politician.

Those are two different species.

Discover more from Beebop's

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.