I keep hearing people talk about what’s happening in Minnesota and other states as if it’s some brand-new problem, something unprecedented, something the US never dealt with before. That just isn’t true. We’ve seen this movie many times in this country, just with different actors and different costumes.

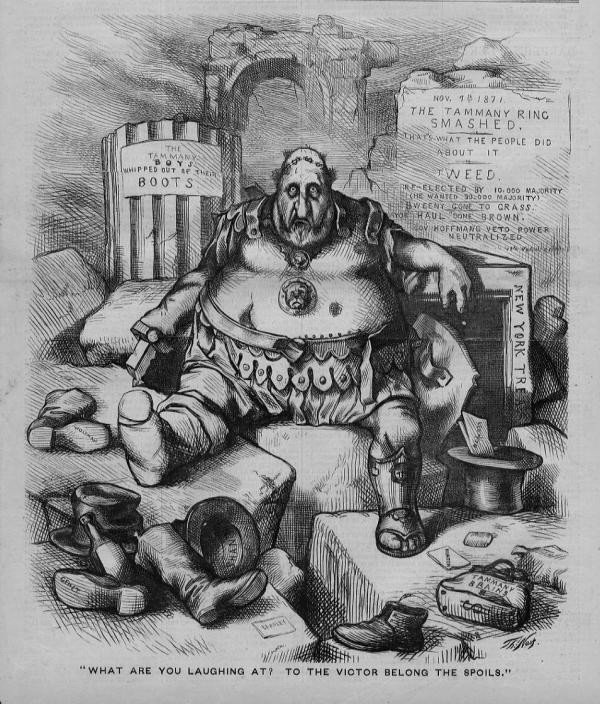

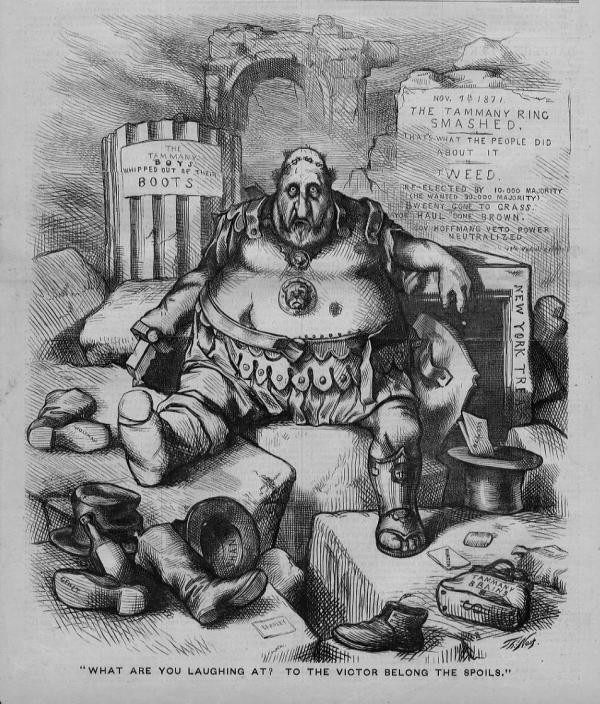

Anytime the government opens the money spigot fast, under the banner of urgency or compassion, and anytime oversight lags behind speed, fraud follows. It’s as American as it gets. Tammany Hall figured it out more than a century ago. The New Deal era saw it when jobs programs and contracts exploded faster than accountability. The Savings and Loan crisis proved you didn’t need street criminals to loot a system, just insiders who understood the rules well enough to bend them. Medicare and Medicaid fraud showed how paperwork could be weaponized at scale. Different decades, same playbook.

What’s happening now fits that exact pattern. Emergency funds. Layers of intermediaries. Trust placed in organizations that look good on paper. Audits that come long after the checks clear. People telling themselves they’re gaming “the system,” not hurting real people. That mindset has always been the gasoline.

I vividly remember a moment years ago that helped this click for me on a very human level. I once asked a longtime customer in my store—a Russian immigrant and a genuinely great guy—something I probably wouldn’t have asked just anyone. We had known each other long enough to speak frankly. One day we got into a conversation about Soviet-era culture, and I asked him why so many Russians were viewed as corrupt or dishonest.

His answer caught me completely off guard.

“Because we are,” he said.

I remember saying, “What?” almost reflexively. He went on to explain that when you are raised in a culture where the only way to survive is to game the system, that behavior becomes ingrained. It isn’t even seen as wrong. It’s seen as normal.

Then he gave me an example I’ve never forgotten. In this country, if you want a nice roast beef for your family, you go into one of the many supermarkets near your house and pick one out. In Soviet Russia, you go to the local butcher shop, bribe the butcher, and meet him out back to get the one he decides to give you. That isn’t corruption in that world—it’s survival.

That conversation stuck with me because it stripped the politics out of it. It wasn’t about ideology. It was about incentives, habits, and learned behavior.

Now let me be very clear, because this matters. Explaining how people learn these behaviors is not excusing them. Fraud is still fraud. Theft is still theft. The people committing these crimes know exactly what they’re doing, and they know it’s wrong. Background and culture can explain behavior, but they do not justify it, and they do not erase personal responsibility. Every person who signs a fake document or steals public money owns that choice, full stop.

Here’s where today feels different, and this is the part we’re not supposed to say out loud. In Minnesota and other states, a large share of this fraud is being carried out by people we invited into our country and quickly placed into systems built on trust, speed, and good intentions. That’s not an attack on immigrants as people. It’s a criticism of policy, vetting, and the fantasy that massive government programs can absorb large populations overnight without being exploited.

America has always welcomed newcomers. That’s one of our strengths. But historically, assimilation happened slowly. Communities formed, norms were learned, accountability followed proximity. What we’re doing now is different. We’re dropping people—often from countries where government corruption is normal, expected, even necessary for survival—straight into complex public funding systems and acting shocked when they exploit what they see.

If you grow up in a place where the government is something you work around instead of with, you don’t suddenly develop civic trust because you crossed a border. You respond to incentives. Everyone does. That’s human nature, not ideology.

Add politics, votes, and money into the mix and soon you have one side defending the bad behavior as if there is nothing to see here.

The uncomfortable truth is that these fraud schemes don’t succeed because people are evil. They succeed because systems are naïve. They assume shared values, shared norms, and shared fear of consequences. When those assumptions are wrong, fraud isn’t an exception—it becomes a business model.

And a few years or even months from now, this will be out of the news cycle, we will forget it ever happened and we’ll repeat it again under a new program with a new name.

We don’t have a compassion problem. We have a realism problem. Helping people and protecting taxpayers are not opposites. They are supposed to be partners. When we forget that, history doesn’t just rhyme—it repeats itself almost word for word.

We’ve seen this before. The only question is whether we’re willing to admit it this time, or whether we’ll pretend it’s all a mystery until the next crisis comes along.

Discover more from Beebop's

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.