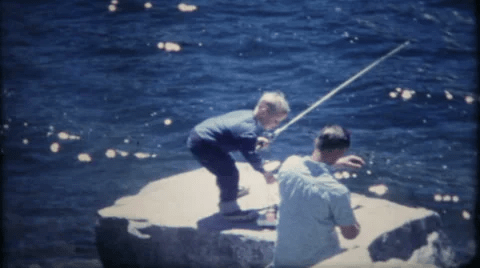

Some of the earliest lessons I remember didn’t come from school or church. They came from my father, usually during our many fishing trips between about 1966 and 1969, when I was roughly 9 to 12 years old, in the form of long lectures that, at the time, I didn’t fully appreciate.

We’d be standing there quietly, lines in the water, not much happening — which was usually his cue. Out of nowhere, he’d start talking about history. Not the polished, textbook version, but the uncomfortable parts people tend to skip over.

He talked a lot about how Black Americans and Native Americans were treated in this country. He didn’t sugarcoat it. He talked about slavery, segregation, stolen land, broken treaties, and how entire groups of people were pushed aside once they were no longer convenient. Looking back, I realize he wasn’t trying to make me feel guilty — he was trying to make me aware.

On those same fishing trips in the late 1960s, he also talked about World War II, and especially about how the Jewish people were almost annihilated. He explained that it didn’t start with camps or ovens. It started with language, labels, separation, and the slow normalization of “us versus them.” In many cases, people didn’t see it coming because they assumed civilized societies couldn’t slide that far. They were wrong.

He also shared stories from his own life. One that stuck with me was how, growing up years earlier, he wasn’t allowed to attend an Irish school — not because of anything he had done, but simply because he was Italian. He didn’t tell that story with bitterness. He told it as fact. To him, it was just another example of how immigrant groups once had to navigate a country that hadn’t fully decided it wanted them yet.

At the time — as a kid in the late 1960s — I listened, but I also remember thinking, “What does this have to do with me and the times we live in?”

“All that stuff happened a long time ago.”

I didn’t realize then how often I would see those same patterns play out — not as hatred, but as survival instincts.

One early experience stands out.

In 1970, when I was 13, my older brother — who was 23 at the time — had just started working as a teacher in an all-Black school in Philadelphia. He and another teacher were taking a group of students on a camping trip to the Poconos and asked if I wanted to come along. I said sure.

You have to understand the context. In 1970, I was raised in an all-white neighborhood, went to an all-white grammar school, and had never — and I mean never — had any interaction with Black kids or even urban adults at that point in my life.

The trip went fine until one night before bedtime. About a dozen Black boys my age and I were all in the tent together, each of us holding a flashlight, which immediately turned the tent into a low-budget planetarium. Boys being boys, things got loud and playful.

Then they started playing a game I had never heard of.

It was called the Dozens.

The Dozens is a long-standing verbal game in Black culture where young boys — and sometimes adults — trade exaggerated, over-the-top insults, often involving family members, especially mothers. The insults aren’t meant to be literal or cruel. They’re meant to be clever, funny, and creative — a kind of verbal sparring that builds status, confidence, and belonging.

They were going around in a circle, each taking a turn, and after each insult the tent would roar with laughter. It was loud, playful, and clearly a game they all understood.

When the boy next to me finished, I assumed it was my turn and jumped in with one.

Oops.

Big mistake.

Every flashlight snapped on and pointed straight at me. Someone said sharply, “What are you talking about? This game doesn’t include you.”

Message received.

I quickly realized I had crossed an invisible cultural boundary I didn’t even know existed. Using whatever negotiating skill a 13-year-old has, I apologized, backed off, and got myself out of the situation.

Nothing bad happened — but the lesson stayed with me.

That moment taught me something no lecture ever could: when people grow up separated, even harmless interaction can go sideways — not because anyone is bad, but because survival creates tight circles.

As I got older, I began to see that same instinct play out in adult life.

In the 1970s, early in my career, an Italian friend once said to me, “Rich, ever notice what all the executives have in common here?” I didn’t know what he meant at first. Then he introduced me to a word I had never heard before: They are all WASPs he said.

White. Anglo-Saxon. Protestant.

Once it was pointed out, I couldn’t unsee it. Same backgrounds. Same schools. Same social circles. Not because someone held a meeting to exclude others, but because power tends to reproduce what already feels safe and familiar.

I didn’t see it as hatred. I saw it as another form of survival — people protecting what had worked for them in a world that wasn’t always welcoming to outsiders.

Fast forward a few years.

In 1978, when I was 21, I heard a senior executive casually use the phrase “typical Italian” within earshot of me while referring to another employee. It wasn’t said angrily. It was said comfortably — as shorthand. And that’s when I realized those old patterns weren’t gone. They had just become quieter.

A few years later, in 1982, when I was 25, I was working in New York City and saw the same instinct expressed differently. Jewish people often stuck together. They did business with each other, referred each other, and supported each other.

I once asked a Jewish boss how he rose so quickly to such a high level. He answered honestly. He said he was personal friends with all the Jewish buyers for the major department stores with buying offices in New York. When he came to our company, they switched suppliers.

That wasn’t corruption. It was community — built for survival.

Years later still, in 2005, when I was 48, I opened my own store in a Mennonite town and encountered the same instinct in a quieter, more subtle form.

The town was polite. Courteous. Orderly. People nodded, smiled, and wished you a good day. But beneath that surface was a strong internal cohesion that was hard to miss. The older Mennonites almost never shopped in my store. Not once in a while — almost never. There were no confrontations, no harsh words, no signs on doors. Just absence.

Over time, it became clear that commerce, trust, and daily life flowed inward, not outward. They supported their own businesses, their own tradespeople, their own networks — families who had known each other for generations. From their perspective, that wasn’t prejudice. It was continuity. It was how a community that had survived persecution, migration, and isolation protected itself from disappearing.

From the outside, though, it felt familiar. Polite on the surface. Closed underneath.

Not hostility — just an inward-looking world shaped by its own long history of survival.

Different groups. Different backgrounds. Same instinct.

And that’s when my father’s lessons from the late 1960s finally made sense.

Every group you see in this story — Italians, Irish, Jews, Mennonites, Black Americans, WASPs — were, at one time or another, outsiders. They stuck together because they had to. Community wasn’t a luxury; it was protection.

What makes America great isn’t that those instincts existed. It’s that over time, we built a culture capable of moving beyond them through assimilation — not erasing heritage, but creating shared rules, shared expectations, and shared identity.

That’s also why interracial marriages matter. Not as a political statement, but as a human one. They quietly dissolve tribal boundaries in the most powerful way possible — family. As the world gets smaller and more interconnected, humans don’t survive by tightening circles forever. We survive by widening them.

I don’t resent people for loving their own. That instinct helped them survive.

What matters is what happens after survival is no longer the goal.

Do we keep the walls up — or do we open the door?

After a lifetime of watching this play out, one thing feels clear to me:

The strongest societies don’t survive by staying separate. They survive by learning how to live together.

And that leaves me with the same question my father planted in me all those years ago — not angrily, just honestly:

Why is it so hard for humans to simply live and let live?

Discover more from Beebop's

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.