Insomnia: The Night I Believed My Brain Forgot How to Sleep

I want to tell this story because I know there are people living inside it right now — or watching someone they love live inside it — and they don’t have the language, the framework, or the reassurance I didn’t have when this happened to me.

Back in 2001, I was a confident, successful guy in my early forties. I had a great marriage, a supportive wife, three daughters, both my parents were alive, my career was going well, and I had just bought what I considered my dream house. I was healthy, active, and very much engaged in life. There was no darkness in my circumstances. That matters, because when words like “depression” get used later in this story, I don’t want anyone assuming my life was falling apart. It wasn’t. My life was solid.

Then my body changed — quietly at first, then all at once.

I’ve always been someone who pays close attention to my body — not in a fragile way, but in a practical one. Over the years, that awareness had served me well. It would save me more than once later in life. But in this case, it became the doorway through which fear entered.

The first sign that something was changing came in March of 2001, long before I understood what it meant.

I woke up one morning and put my feet on the floor, expecting nothing out of the ordinary. Instead, I felt something strange under the ball of one foot. The best way I can describe it is this: it felt exactly like the sensation you get when you come off the beach and there’s a clump of sand stuck under the ball of your foot inside your shoe.

I actually lifted my foot and looked, expecting to see something there.

There was nothing.

I rubbed the bottom of my foot. The sensation didn’t change. I walked around a little. Still there. Not pain. Not numbness. Just… wrong. Foreign. Like something didn’t belong.

That feeling hit me like a punch to the chest.

Because this wasn’t just an odd sensation — it was familiar in the worst possible way. My mother had suffered from severe hereditary neuropathy later in life, and I had seen how it began. Subtle. Easy to dismiss at first. Strange sensations that didn’t follow the usual rules. So when that feeling didn’t go away, panic set in fast. Not dramatic panic — quiet, internal panic. The kind where your mind starts racing ahead before you can stop it.

Is this how it starts?

Is this the first sign?

Is this already happening to me?

That’s the part people often miss. It wasn’t just the sensation itself — it was the meaning attached to it. A strange feeling in your foot is one thing. A strange feeling that fits a story you already know by heart is something else entirely. I would later learn this sensation fell under the umbrella of neuropathy, but at the time it wasn’t a diagnosis — it was a question mark with a shadow attached to it.

I didn’t collapse. I didn’t stop functioning. I went to work. I lived my life. But from that day on, something shifted. I started paying closer attention to my body. Maybe too close. Every sensation got logged, compared, evaluated. And once you start monitoring your body like that, it’s very hard to stop.

At the same time, my job was high pressure. Sleep mattered to me. Not in a casual way — in a very real way. Sleep meant clarity. Sleep meant performance. Sleep meant control. I was someone who prided himself on being sharp, reliable, and steady. Losing sleep felt like losing my footing.

Around this same time, I had just purchased what I truly believed was my dream house — a diamond in the rough. A real handyman special on a street and in a neighborhood I had only ever dreamed of owning a home in someday. And I wasn’t just happy about it — I was almost manic with excitement. Obsessed is probably the right word. I couldn’t think about anything else.

The house wasn’t livable yet, not even close. My family was still living in our old home while I worked on the new one, and I spent every free hour I had there — nights, weekends, early mornings — tearing things apart, fixing what I could, learning as I went, pushing myself harder than I probably should have. I’d lie in bed at night planning the next day’s work, replaying ideas in my head, unable to shut my mind off. I was exhausted, but I didn’t feel it at the time. I was running on adrenaline and purpose. I could see what the house was going to become, and I was determined to make it happen for my family.

Then, in September of that year, my back went out — hard. The kind of back injury where you know immediately something isn’t right. That first night, I didn’t sleep at all. Not a minute. The pain was relentless. Every position hurt. I wasn’t alarmed by that. Anyone who’s ever thrown their back out expects a brutal night or two.

The second night wasn’t much better. Still pain. Still no sleep. Again, I wasn’t panicked. I told myself what I’d told myself other times in my life: this will calm down in a few days.

By the third night, the pain began to ease. Not gone, but manageable. I could move more freely. I remember thinking, Tonight will be the night. Tonight I’ll finally sleep.

I didn’t.

I lay there exhausted, staring into the dark, waiting for sleep to arrive — and it never did. That was new. That was unsettling. And that was the exact moment something shifted in my head.

I stopped thinking about my back and started thinking about sleep.

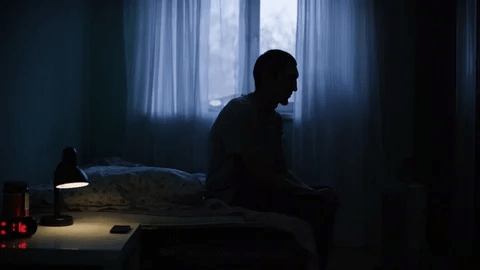

From that point on, nightfall became something I dreaded. The sun going down didn’t bring relief — it brought fear. Evening meant another long stretch of watching the clock, listening to my own breathing, monitoring my body, waiting for something that wouldn’t come. I wasn’t just awake — I was alert. Wired. My heart would pound as soon as I got into bed. The harder I tried to relax, the more awake I became.

People who haven’t lived this don’t understand how dark the nights can get. Lying there for hours, night after night, with no escape. No distraction. Just your thoughts and a body that won’t shut down. I remember begging my wife to take me to the hospital in the middle of the night. Not once — many times.

And here’s the part that still sticks with me.

She would ask, “For what reason?”

And I didn’t have a clear answer.

I wasn’t bleeding. I wasn’t having chest pain. I wasn’t short of breath. I just knew something was terribly wrong. I felt like I was slipping away, like my system was failing, and I couldn’t explain it in a way that made sense to anyone else. That helplessness — knowing you need help but not being able to articulate why — is terrifying.

As the weeks went on, my body entered a state I didn’t understand at the time. My resting heart rate climbed into the high 90s, around 97, while I was doing nothing. Blood tests showed extremely high adrenaline levels. That wasn’t in my head. That was lab work. Doctors became concerned I might have an adrenal tumor or cancer. I was hospitalized and underwent testing where they used medication to shut down my adrenal glands to see how they behaved. They were ruling out something that could literally kill me.

The tests came back negative.

Good news — except I was still trapped inside a body that felt like it was running a marathon at full speed with nowhere to go.

From there, the search widened. Brain MRIs. Full-body tests. Endless blood work. Sleep studies. I remember being told I slept overnight during one of those studies, and I didn’t believe them. I walked out convinced they were just trying to sell me a CPAP machine. I can laugh about that now. I couldn’t then. I couldn’t feel sleep happening, so I assumed it wasn’t happening at all.

Meanwhile, my symptoms piled up. I lost weight fast. I had no appetite. Food stopped tasting like food. I lost my sense of smell. I developed geographic tongue. I had night sweats. I couldn’t focus long enough to watch a movie. Even going to the store felt overwhelming. And every night, without fail, I felt dread settle in as evening approached.

Make no mistake — this was clinical depression.

But it wasn’t the kind people usually imagine.

I had no desire to end my life. I loved my life. I loved my family. I wanted to live. What I wanted was for whatever had taken over my body and brain to stop. This wasn’t sadness about my circumstances. This was exhaustion, fear, and a nervous system that had been pushed too far for too long.

At the same time, I was living alone in our new house, renovating it while my family stayed in our old home. The house smelled awful when we first bought it — old materials, dust, who knows what else. I became convinced it was making me sick. I wore a mask around the house. Looking back, some of that may have been real, and some of it was my brain desperately trying to identify a threat it could point to.

I did what I’ve always done. I researched.

This was early internet days. No filters. No guardrails. Cancer. Adrenal disease. Neurological disorders. Lyme disease. I chased them all. And I noticed something strange. When I stumbled upon an explanation that seemed to fit — even if it was bad news — I felt better. Immediately. Not cured, but calmer. Clearer. Like a switch had been turned off.

What I understand now is that my brain wasn’t afraid of bad answers. It was afraid of not knowing. Uncertainty kept my nervous system locked in fight-or-flight. Certainty, even terrifying certainty, allowed it to stand down — briefly.

Eventually, my job granted me a medical leave. I went out October 1st, 2001, and returned January 1st, 2002. I wasn’t fully better when I came back, but I could function. The timing didn’t help. I was out during the holiday season, and the higher-ups were not happy. That was made very clear to me by my new boss when I returned. Still, I rebuilt myself and went on to stay there another three years — stronger than ever.

I made it through without the medications doctors wanted me on. That’s not a judgment. Medication helps many people. But what saved me was understanding — education I wasn’t getting from the medical profession at the time.

Looking back, I believe what I experienced needs a better name than “depression” or “anxiety.”

Those words carry stigma and misunderstanding. They imply weakness, sadness, or dissatisfaction with life. None of that applied to me. What I experienced fits better under terms like severe nervous-system hyperarousal, adrenal overload, or stress-response collapse — the same physiology soldiers experience in combat zones. Not weakness. Not character failure. A system pushed into survival mode and unable to shut off.

Words matter. When the name itself feels wrong, it isolates people. It makes them feel misunderstood. And misunderstanding is where suffering multiplies.

If you recognize yourself in this — or you’re watching someone you love live through it — please hear this: you are not weak, you are not broken, and you are not alone. A person can have a great life and still have their nervous system overwhelmed. Education, reassurance, and understanding are not optional — they are treatment.

If you’re reading this in the middle of the night, wide awake, scared, watching the clock, convinced something terrible is happening — I want you to know this: I remember those nights. I remember begging for help without being able to explain why. And I also know that the system can reset, the fear can loosen its grip, and clarity can return.

Not overnight.

But it can return.

One of the most important things I eventually learned through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is something so simple it almost sounds impossible when you’re in the middle of it: the brain already knows how to sleep. You don’t have to teach it. You don’t have to force it. You don’t have to monitor it. The more you try to control sleep, the more awake you become. Sleep happens when you stop chasing it.

The brain will sleep when it feels safe again.

Your job isn’t to make sleep happen — it’s to believe it can and let it happen.

And if telling my story gives even one person — or one spouse — enough understanding to loosen their grip just a little, then it’s worth telling.

Because sometimes healing begins the moment you stop fighting your own mind.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please like, subscribe, and click Beebop above to visit my site for more stories, insights, and updates.

Discover more from Beebop's

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.